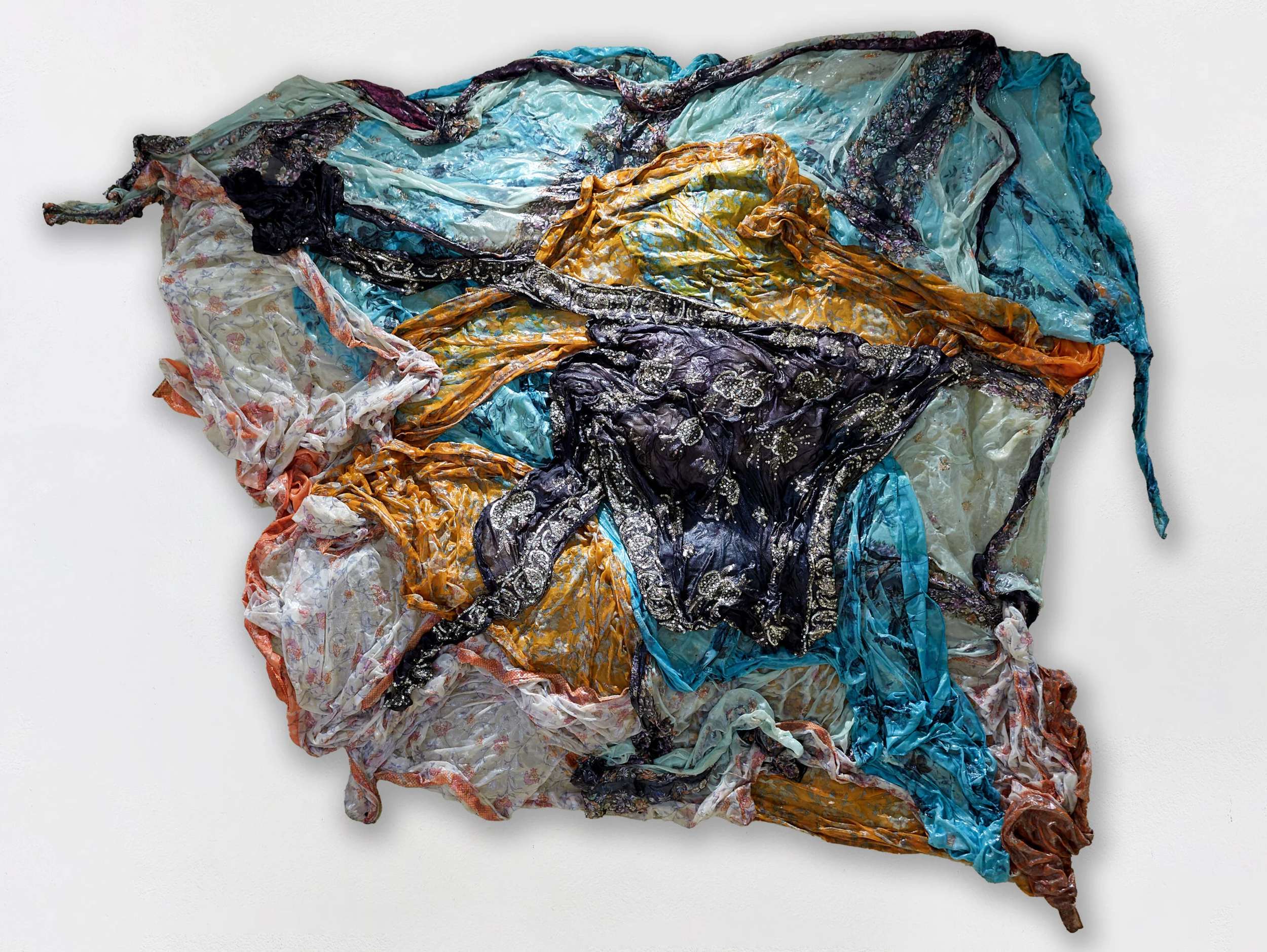

Cheriese Dilrajh, What the seas brought, 2024

As Natural As Daylight

Plants, Memory and The Edge of Belonging

Curated by Yusuf Essop & Jade Nair

Participating artists include: Alka Dass, Cheriese Dilrajh, Hemali Khoosal, Layla Kassan, Shamil Balram, Talia Ramkilawan, Tyra Naidoo, and Zenaéca Singh.

Main Gallery: 20.11.25 – 22.01.26

In 1996, Ronnie Govender, renowned South African Indian playwright, community theatre organiser, and Cato Manor native, published At the Edge and Other Cato Manor Stories. Set largely in the 1940s–50s, the collection tracks the years leading up to the destruction of Cato Manor and the forced removals under the Apartheid government’s Group Areas Act. Cato Manor was built by freed indentured labourers and their descendants, first brought to Natal to work sugarcane plantations. Govender’s prose, shaped by oral storytelling and theatre, maps what Duncan Brown calls an “unofficial cartography” of belonging and everyday ingenuity against the state’s cartography of separation, dispossession, and control. It renders a “carnivalesque chorus of voices,” attentive to place, plant life, ritual, humour, and grief, while refusing to essentialise “Indian” identity or smooth over prejudice and conflict.

More than literature, the book functions as a text-site of memory. As Rajendra Chetty notes, it participates in post-1994 nation-making by recalling multiracial coexistence alongside the injuries of Apartheid, staging memory as an active, ethical practice—akin to a community’s living archive. Govender’s insistence on naming streets, trees, gardens, and textures of life becomes a method of remapping South African belonging from the ground up.

Plant life threads the stories in sensuous detail: herbs, fruit, and vegetables in market and domestic gardens; camphor, syringa, and turmeric in traditional medicine; sugarcane worked by indentured labourers; the saturated greens of the “lush sub-tropica.” These are not mere backdrops but narrative devices showing how so-called “exotics” took root and came to define parts of the South African landscape, transforming exoticism into an idiom of belonging. As Brown observes, vegetation “intrudes” into consciousness and becomes the medium through which characters claim place and self. There is poignancy in a people carried across the Indian Ocean under colonial violence who also carried the plant life of home; that these plants survived “months’ long” journeys speaks to resilience and a desire for continuity.

The Indian migrant story is inseparable from plant life and agricultural labour. The early economy fixed Indians in sugar monoculture while neighbourhoods nurtured polyculture - herbs, fruit, vegetables - for kitchens, markets, and ritual life. Govender juxtaposes administered landscapes with small plots whose names, smells, and textures become proofs of existence even after removals. This is the everyday politics of space, where gardens assert continuity within rupture.

This planted world matters for two reasons. First, it materialises migration: seeds and the knowledge to cultivate them travel with people, transplanting foodways, medicines, and ritual calendars into new soil. Second, it marks presence: market and home gardens counter colonial monoculture with diversified ecologies of sustenance, care, and aesthetic order - literally “setting down roots” against the state’s will to uproot.

Thinking of identity as both being and becoming, it is anchored in shared memories—indenture, neighbourhood ritual, language traces, food—yet continually remade by location, law, and media. In the post-1994 public sphere, Indian identities span a continuum: from defensive essentialisms that strategically claim ‘Indianness’ to counter-essentialist, hybrid positions foregrounding South Africanness and coalition—each shaped by power, representation, and translation.

As Natural As Daylight uses Govender’s garden to think through these dynamics now. The garden works as archive (a sensory memory-technology), as position (rootedness forged through care and cultivation rather than blood or myth), and as question (what “South African” means when an imagined India persists and present-tense belonging remains contested). The exhibition proposes the garden as method and metaphor: reading Govender not to reconstruct Cato Manor, but to show how plants—named, tended, exchanged—compose a theory of belonging for a South Africa wrestling with racialised histories, uneven recognition, and plural futures, where being remains accountable to becoming.